This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

“We are stardust, we are golden, and we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

So sang Joni Mitchell back in the idealistic counter-cultural 1960s, and “Woodstock,” the song she wrote about that desire to return to the garden, became an anthem of that generation.

Back to the garden! Eden, that is, not vegetable. The desire of the human heart to return to paradise, to return to the place of innocence and wholeness, back to whatever it was we had before we lost it.

For those who came of age in that decade, at least some of them, it all seemed so simple: just will it, and it is so. We’re stardust and golden, and there’s nothing we can’t do if we set our minds on it. We can change the world, and we will, and it will turn out just fine. Just you wait.

But the impulse to undo original sin is a perennial and fierce one in the human spirit, not limited to one generation or time or place.

Attain perfect social justice and equality, the worker’s paradise, and all shall be well. Attain perfect liberty, equality, fraternity, and all shall be well. Attain perfect sexual liberty, and all shall be well. And so at Woodstock and elsewhere they did indeed walk around naked and without shame (Gen 2: 25), and … well …

All did not turn out so well, did it? The worker’s paradise turned into the Soviet gulag, the glorious French Revolution ended in Terror, the sexual revolution ended in—well, it hasn’t exactly ended yet, but I don’t see too many signs of all being well on that front these days, do you?

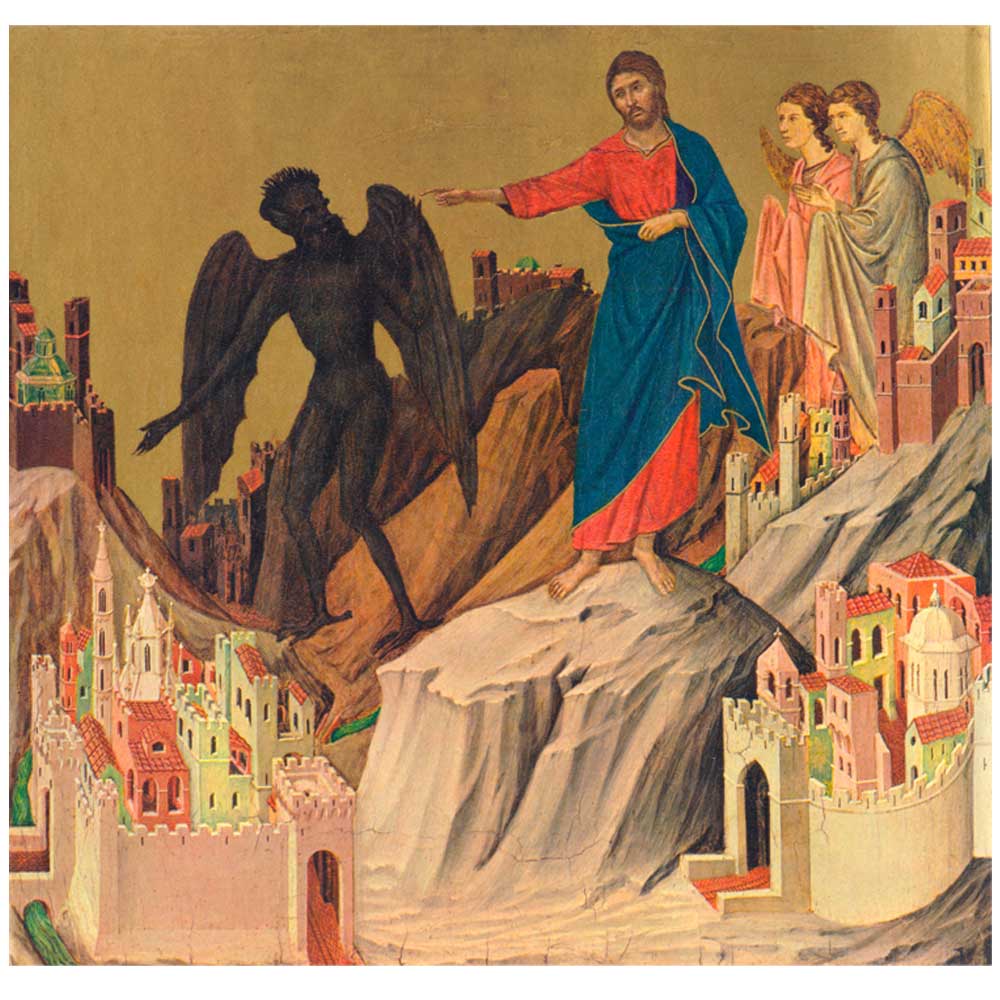

So what’s all this got to do with the “Word Made Flesh” in February 2018? The First Sunday of Lent this year brings us Mark’s account of Jesus in the desert, an account that is quite different from Matthew’s and Luke’s.

Like much of Mark, it is very short. Jesus went into the desert for 40 days, was tempted by Satan, was with the wild beasts, and the angels waited on him. That’s it!

Its very brevity contains a profound revelation of God. Jesus has gone “back to the garden” in truth in this Gospel, but fallen man has made the garden into a desert. Nonetheless he is back, and in him paradise is restored.

He is with the beasts and the angels—both higher creation and lower are one with him.

He is tempted by the devil, as were Adam and Eve, but unlike them does not sin. The specific temptations are not given here, because that is not the point Mark is making.

Jesus is the new Adam come to bring all humanity back to the garden, back to the state of innocence and communion that was ours before the Fall. But it is not a matter of simply willing it and it is so.

The garden is no garden any more, but a desert. We cannot will that away—the harm and hurt done to creation, done to human beings made in God’s image, done to one another, done to ourselves—all of this is the wilderness of sin that Jesus has come to heal and restore.

So, it is Lent, and it is time once again to go out with Jesus into that desert garden for forty days. What for? What good does it do? What is this Lenten desert journey about?

Lent is not a time to just go out there to brood on the desert and its ugliness, to fume and fret about our own sins, nor (God forbid!) the sins of others and how we’ve all worked together so well to make the desert particularly arid and bleak this year.

Nor is Lent a time to try to make that desert a garden by sheer dint of our own hard work and gumption: if we just haul enough sacks of composting soil and water cans out here, surely something will bloom!

The futile effort of self-cultivation, of trying to at least make our little corner of the desert fruitful by our own hard work and sweat—that’s not what Lent or any other time of year is about, either.

What is it about? Well, it’s about Jesus. Jesus has gone out into the desert of the world, the desert of humanity, the desert of sin and sorrow and all the frailties and failures of our poor fallen state. And where Jesus is, is Paradise. Where Jesus is, is the garden. Where Jesus is, is the Kingdom.

Do we believe that? It seems to me that is the key question not only for Lent but for life.

We live in a world that has at least some desert qualities to it all the time. Some people’s lives are much more barren and desolate than others, but none of us are living in the Garden of Eden, to say the least.

And even if we count ourselves as blessed people surrounded by much beauty and tangible goodness in our own lives, the world we live in has much suffering and great evil, and we cannot help but be grieved by it.

And Jesus has come to that very world. At Easter we enter deeply and joyously into the reality, the truth, of just what he has done to restore the garden to us, to make our lives beautiful and whole again. But in Lent it seems to me that the call is to simply be with him in the world as it is.

And if we approach it that way, the customary practices of Lent fall into place with a certain naturalness, an obvious meaning and value: prayer, fasting, almsgiving.

We live in the desert: we grieve over what is lost, over what has been marred (fasting); we lift our voices to God to continue and complete his work of saving love (prayer), and we do our little part, whatever we can do, to redress the pains, heal the hurts of the world (almsgiving).

But in all of this, it is being with Jesus that makes our Lent fruitful, makes our lives joyful even in the midst of the desert. In Jesus there is an eternal garden always in full blossom, in him there is color and scent and nurture, beauty beyond description.

And the only way “back to the garden” is the way into his heart in the heart of the world, just as it is, waiting upon him as we go through the desert, waiting for him to complete the great work of Easter in us and in all, waiting for him to make all creation just as it will be in the Kingdom of heaven forever.