The pilgrim has to walk the road of self-denial and self-discipline.

Last month, in part one of this article, Amy explained moderation and temperance.

◈◈◈

How does one eat for the glory of God?

To eat in accordance with reason is to eat what is needed to sustain the life of the body. It is even more virtuous, however, as the Dictionary of Moral Theology notes, to “take food and drink to obey the Lord or to give glory to God than simply to satisfy a need.”

So, for example, we might fast or feast to honour a certain liturgical season with our bodies. Our way of eating during Lent, for example, might impose minor hardship on the body, a little more fatigue than we would otherwise experience.

Our way of eating during Easter might exceed the limits of what our body requires. But we are, in neither case, following the direction of our own preferences but rather attempting to bring our bodies into harmony with the liturgical life of the Church.

This is why sometimes here at Madonna House, if someone pulls out a treat on any old day in Ordinary Time, they will make an excuse, saying, “It’s for the feast of St. So-and-So!” This is a bit of a joke, a knowing nod to the fact that we are being a little intemperate. But the joke contains a truth, which is that we are trying to make sure our feasting is not just for the sake of enjoyment, but rather something we are doing for the glory of God.

Catherine Doherty speaks eloquently about how our freedom to follow the Lord in the pilgrimage of life presupposes restraint in our appetites: The pilgrim has to face the road of pleasure. Obviously, a pilgrim is not going to indulge in a lot of pleasures, even legitimate ones like smoking, for instance. Smoking is injurious to health, but that is not the main point for the pilgrim.

What is important is not giving in to desires that are not blessed by God. The pilgrim has to walk the road of self-denial and self-discipline. Smoking, liquor, gambling—these and other cravings need to be controlled. He walks the road of self-discipline and of surrender of pleasures because he loves God. This does not mean that pilgrims don’t marry. It doesn’t mean they don’t drink occasionally. It doesn’t mean that they don’t play bingo.

No. It means that the self-discipline is deep and profound because the pilgrim sees the road he has to travel. He knows that it is the road of Christ. He knows that he must be interiorly free to travel it and that these so-called “passions,” as they were called in the old spiritual books, restrain and crush him. *

We can only be moderate in the use of created goods if these are not, by nature, sinful or harmful.

In the same way as it is not virtuous to be moderately murderous, or moderately slanderous, we cannot use pornography moderately: we must abstain from it completely because it is by nature something that is destructive to the human person and society. Moderation is only virtuous when it applies to the use of what is good.

This is where a distinction between moderation and temperance may apply. Sometimes in order to be “temperate” we have to abstain, not merely “be moderate.” Remember that the Temperance Societies of the 1800s did not advocate moderation but rather abstinence from alcohol.

The reality is that many people cannot hope to achieve moderation in their use of alcohol as they are predisposed, genetically or through the development of bad habits, to be incapable of this. One drink will lead to another. Alcohol is a harmful and destructive substance in their lives, and, for them, moderation in its use is impossible. In such cases, abstinence and support are the only routes to temperance.

I know of several people who have come to the same conclusion when it comes to their use of sugar. We must start, of course, by trying to be moderate. But if we find we are unable to do this, if we find we seem to be developing an addiction, we might have to abstain and get help. This can also apply to other things, like internet use.

It is also possible to be immoderately or intemperately abstinent. According to the Dictionary of Moral Theology, “one may sin against temperance also by defect, by fleeing the enjoyment of taste or touch, although reason may recognize its legitimate necessity, and the light of faith may counsel it.”

So, while overeating is an obvious example of intemperance, we are also not being temperate if we deliberately spoil our food or refuse to eat what is needed to keep us in good health.

It is also possible to fast in a way that is intemperate. Moderation in fasting often means submitting to the common way things are done, choosing to be hidden rather than undertaking an extreme and noticeable asceticism.

If I’m at Madonna House, and I choose to do a radical fast during Lent, such as eliminating all protein from my diet, then not only may I run the risk of incapacitating myself for our shared work, but I also run a high risk of vainglory for doing something that others will certainly notice.

Often it is more useful for my soul to do something that does require me to curb my appetites but which nobody else ever notices, because what I’m doing is not remarkably different from what others may do.

How do I regain temperance when I have lost it?

Intemperance in matters of food leads, as the Dictionary of Moral Theology notes, to “weakness of will,” and I find that experience bears this out. In the days of Christmas and Easter, we eat richer foods, and these may be more available than at other times.

After a few days of overindulgence, I notice that my will becomes weaker in other areas. Maybe I let go of seeking the Lord in solitude and prayer. Maybe I start letting my preferences rule in other areas of my life: I want to go on a hike only with these people or play a game with those people, etc. The more I let my desires rule my life, the more I develop the habit of intemperance and the more difficult it is to start fresh.

Something I have found helpful when I’m trying to regain a foothold after Christmas or Easter, and my capacity for self-restraint is kaput, is to make a little commitment. Maybe I can’t successfully make a commitment about the big areas where I am tested in my self-restraint, but there is always some small area where I can make a choice and stick to it.

For example, I might say, for the glory of God and to re-establish his authority in my soul, I won’t use the white sugar in the middle of the table for any reason during the next 30 days. Somehow just this little choice gives me the capacity to make other, more important choices. And the battle for temperance begins again.

◈◈◈

God’s mercy

The community I discerned with before joining Madonna House was in the middle of a big Canadian city. Our church was open most of the day, and people could walk in from the street.

One person who came in frequently was a man named Raphael. He was unkempt and a bit intimidating. He would stagger boldly to the front of the chapel when we were in Adoration and start yelling at the Blessed Sacrament in French. When he’d had it out with Our Lord for long enough, he’d move over to the statue of Our Lady and have it out with her too.

“Why do you leave me this way?” he would shout. His prayers were true prayers, extremely heartfelt groanings from the depths of a heart that knew its own frailty and failure, and that desperately yearned to be free from alcoholism.

When he prayed, it made me pray too. “Yes, Lord, set him free! Why do you leave him this way?” Or on other days, “Yes, Lord, set us all free! Why do you leave us this way?”

I liked to talk to Raphael. He knew the Church Fathers extremely well, and I learned that he had been a Trappist monk in his early adulthood. Now he always carried around a plastic water bottle full of something foul, and as often as we tried to say “You can’t drink in here,” he just seemed to keep on doing it automatically and reflexively, as if he didn’t even notice what he was doing.

One day, Raphael had a heart attack. One of the brothers drove him to the hospital, and the doctor told him, “If you don’t get sober, you will be dead in six months.” That scared him straight: he went to rehab, and when he got out, he was a changed man. He was hidden in the midst of the Sunday congregation, wearing a nice suit. For awhile I didn’t notice that he had returned from rehab because he was so unlike his former self.

This lasted for a little while, but not for long. A year or so later, things looked much as they had before rehab. “Why do you leave me this way?” he would yell again at the Lord. Well, like St. Paul, like the Publican, the answer seemed clear: because this way, you know how much you need me.

I doubt that Raphael is still alive. If he is, maybe I should have changed his name. But in any case, I think he lived his “intemperance” in such a way that the Kingdom of Heaven belongs to him. I hope he’ll let me in, some day.

Where can the weak find a place of firm security and peace, except in the wounds of the Savior? Indeed, the more secure is my place there, the more he can do to help me. … I may have sinned gravely. My conscience would be distressed, but it would not be in turmoil … what sin is there so deadly that it cannot be pardoned by the death of Christ? **

*Adapted fromStrannik, Madonna House Publications, 1991, p. 74.

**From a sermon on the Song of Songs by St. Bernard.

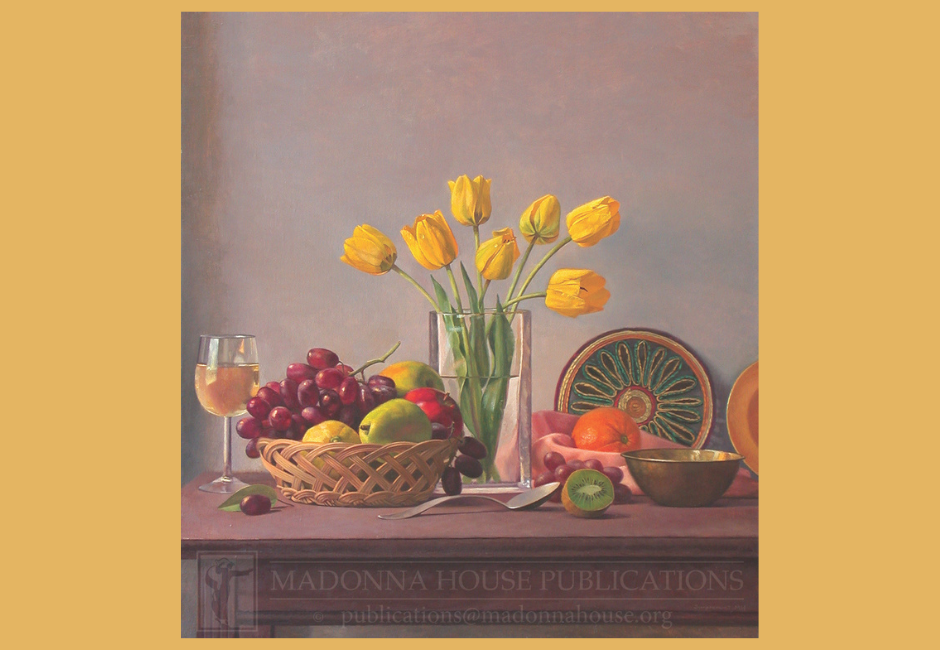

Tulips, Fruit and Wine painting by ©Donna Surprenant, Madonna House