This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

“Michael, you opened your eyes!”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Michael, I saw you open your eyes.”

“I’m telling you: I did not open my eyes!”

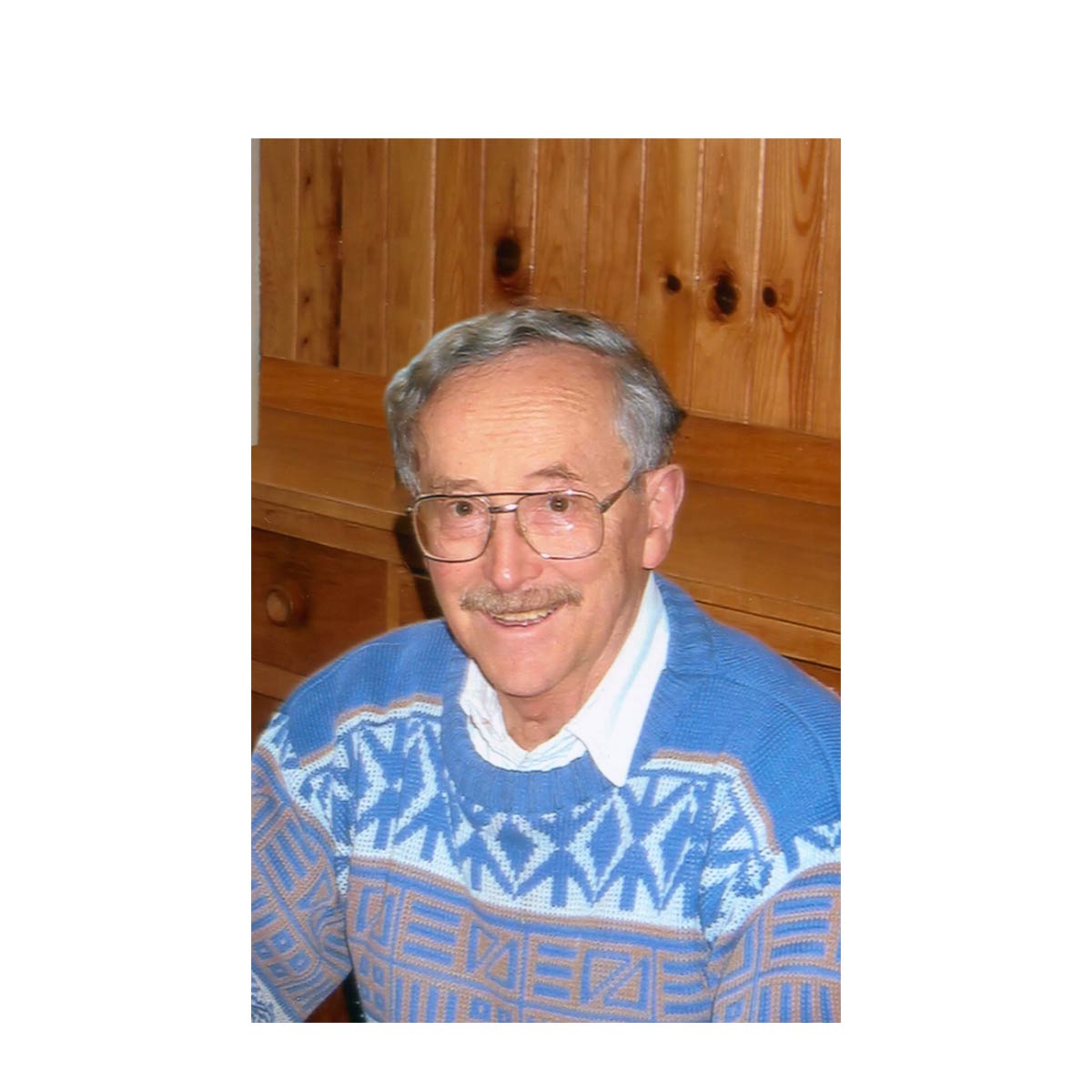

Following serious eye surgery, Michael was prescribed at least three different kinds of drops three times a day, and I was the man assigned to the job. Michael was asked to keep his eyes closed for five minutes each time. He wanted to take the drops in his favorite corner of the specials dining room at St. Mary’s, but this location was a busy spot. Inevitably Michael would get distracted and look up.

In an attempt to improve his concentration, I offered to read aloud the scripture passages and a short life of the saint for the following day’s Mass.

Sometimes there would be silence before the next interval of drops, allowing the words from the Bible to sink in, just like the medication. Michael would usually sigh. The whole encounter wouldn’t last more than 15 minutes, but there came to be a bond between us—resting on a foundation of Scripture and Tradition.

Michael was a man of prayer. The easy chair in his room was buttressed by a pile of missalettes, rosary beads and copies of a conservative Catholic periodical. His bookshelf was jammed with old breviaries, and his desk was littered with holy cards. Often when I would knock on his door, he would either be saying the rosary silently or nodding off with the beads in his hand.

I would often drive Michael to doctors’ appointments. Our times together were precious moments to reflect on our life in the apostolate, news of the day and even, at times, our own personal struggles. Michael would often lament the fact he could hardly finish reading an article without nodding off and that he no longer had the get-up-and-go he once had before he turned—90!

For most of his life, Michael had a lot of get-up-and-go. Before joining Madonna House at the age of thirty, he earned a B.S. in general agriculture and a Master’s degree in food technology. He had a few different jobs in that field, the last one being teaching at the University of Massachusetts.

And then, in the 1950s, inspired by an article about Madonna House in the newspaper, Our Sunday Visitor, he decided to visit here.

In a letter about his impressions at that time, Michael wrote that he was captivated by our Russian-born founder Catherine Doherty. And he was convinced by her words that “I must die to self, leave everything behind me, go into the market place and leaven the masses, and see Christ in people, especially abused minority groups, homeless transients, the poor and unfortunate of all kinds.”

During that first visit also, Michael, who had grown up in a wealthy family in Chile, accepted working with his hands.

In another letter he wrote, “You get to discover the tremendous dignity of manual labor. Fr. Brière, one of the priests, summed it in four words. ‘Our Lord did it.’ Guests are expected to join in the work which includes such jobs as mowing the lawn, hoeing in the vegetable garden, picking berries, and washing dishes. Somehow, you find you do not mind it at all.”

During the course of his years at Madonna House Michael did his share of manual work particularly at the farm. He helped till the poor land, harvest crops, and worked with others on major projects.

The photo albums at our farm, St. Benedict Acres, contain photos of him with our other pioneers, now mostly deceased, working and relaxing together. They all shared in the dream of the founder that we live as much as possible from food we grow ourselves.

As a member of the community, he also served in Winslow, Arizona and was director of Marian Centre Regina, where, among other things, he ran a soup kitchen and founded a co-op.

Then back in Combermere, he became registrar of men, the first contact for men wanting to spend time with the community. His office was a drafty wooden porch attached to a cabin housing a men’s dormitory, both without central heating or running water.

Finally, of course, Michael grew old. It is then that I often saw him in the chapel long before Mass or prayers were to begin.

Like so many men, Michael loved cars, and it had been hard to give up his license. But later on, when walking became more and more difficult, he was given a scooter.

He proudly parked his new set of wheels in the hallway outside his room, making sure it was plugged in overnight for a quick start in the morning. He loved to ride from one end of the big St. Mary’s building to the other—going fast.

But after a while, he complained that the scooter didn’t seem to have that much punch. It turns out that the scooter had been “fixed” to keep Michael from going too fast.

Even late in his life, Michael faithfully continued to be present at evening teatime, a time when we relax together, or at least in the same space. Some staff members choose to sit around a table chatting or playing cards or board games. Others, the more introverted types, read or work quietly on puzzles or crafts. Michael spent his time almost exclusively tucked away in the corner at the magazine rack. He loved to read, especially Catholic periodicals.

Michael’s favorite sport was tennis. As a young man in Chile, he had played it frequently. In Combermere, of course, opportunities were rare, but he continued to watch it on television.

He was thrilled with the excitement of the game and he recorded the annual tournaments on VHS tapes. These tapes Michael was reluctant to part with even twenty years after the fact and when VHS players became as rare as cassette tape players.

In the last few years of his life Michael chose to take his holidays at a retirement home in Ottawa that offered short-term stays. Michael always asked to take it in September to coincide with the U.S. Open.

Two things were non-negotiable: a TV in his room so he could watch the games and access to Mass. He seemed oblivious to other things, such as the view from the room window, the weather, and even world events. What mattered was tennis in New York.

As is probably obvious in this article, I only got to know Michael in the last few years of his life. My experience with him was in the years when he was hunched over, struggling to walk with a cane, and squinting to read the newspaper, all the while with ever-diminishing energy.

He regretted what he could no longer do but accepted God’s will and work in him as he underwent old age. I saw in him the dignity in growing older and wiser, the path of many of our elders who chose to stick it out with the community.

It was a privilege to accompany Michael on this last part of his journey. And seeing his life in Madonna House is giving me courage to stick things out through thick and thin.