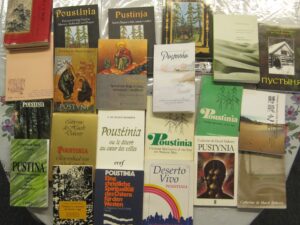

Translated into sixteen languages…a spiritual classic.

In 1974, Fr. Robert Wild, who compiled the spiritual classic Poustinia from talks and staff letters by Catherine Doherty, went to ask her permission to submit the manuscript to Ave Maria Press. “Go ahead,” she told him. “But no one will read it. North Americans aren’t interested in that sort of thing.”

She couldn’t have been more wrong.

In 1962 Catherine introduced the concept of poustinia, the Russian word for “desert,” to the Madonna House community. As she described it, this Russian tradition consisted of going apart to pray and fast in silence and solitude in order to intercede for the world and to listen for God’s word through Scripture and in one’s heart.

Poustiniks differ from hermits in that they have a close connection with the village, monastery, or other community with whom they are associated. The poustinik’s prayer is his or her form of service, but they can also be called forth to help in other ways, as needed.

Catherine herself had for some time been spending Fridays in silence and solitude, listening to the Lord and sharing with her spiritual family the fruits of her meditations.

Now she presented the concept as a way of praying for the Second Vatican Council. In an old farmhouse at Marian Meadows, one of the MH properties, a room was set up where members of the community would go to pray for 24 hours at a time. There was a hard bed, a table and chair, and on the wall a cross without a corpus. The only book was the Bible, the word of God,

On October 11, 1962, the opening day of Vatican II, the whole community made a walking pilgrimage to Marian Meadows. Two women, Mary Davis and Josephine Halfman, became the first Madonna House members to “make a poustinia.” By the following spring, most of the staff had spent at least one twenty-four-hour period in silence and solitude.

The need was great. The 1960s were years of confusion and upheaval in the Catholic Church, destabilized by an attempt to redefine every aspect of religious life and practice in terms of the modern world.

Priests and nuns left their rectories and convents for the ghettos in their desire to remedy social injustices by applying gospel principles. In many cases, they burned out or lost their way, losing faith in their original vocations.

Catherine, who had always insisted that the gospel had to be incarnated and who had herself been a pioneer in the fight for racial equality, understood that without prayer, without listening for the voice of God, one ran the risk of mistaking one’s own will for that of God. Poustinia became a response to misguided activism.

For the youth, especially, these were years of spiritual searching — years of pilgrimage, of experimentation, of the “Jesus people” and the hippie movement. Catherine had a special love for the hippies and welcomed the young people who flocked to Madonna House.

She was careful, however, not to let the poustinia become a fad. Guests had to be anchored, first and foremost, in the stability of everyday life and service. Like everyone else, they were only allowed to go to the poustinia with the consent of a spiritual director.

For the exhausted staff, the poustinia offered the opportunity to recharge their spiritual batteries.

By 1965, all the Madonna House missions had a room set aside as a poustinia. In Combermere, construction began on a poustinia next to Catherine’s cabin. Fr. Francis Martin, a former Trappist monk and a Scripture scholar, came to live, work, and pray at the Marian Meadows poustinia.

The fruit of Catherine’s own poustinias found expression in the direction Madonna House life began to take. “There was a tangible shift,” said a staff member, “towards inner transformation.” The poem “Journey Inward” is undated, but expresses the sense of inward pilgrimage, of kenosis (self-emptying), that was increasingly becoming a foundation of MH spirituality:

Somewhere along

The road of life

By the grace of

God,

My soul woke up

And its hunger

Now,

Became a fire…*

By 1967, four poustinias in Combermere, including Catherine’s, were in constant use both by members of the community and by visitors.

Over the next few years, two other aspects of the poustinia emerged. The first involved three laywomen and three priests who discerned a vocation to live three days in the poustinia and to spend the rest of the week serving and sharing with the rest of the community the graces they had received.

From February to August 1973, Catherine met with them regularly, forming them in a spirituality that seemed to pour forth from her spirit, with neither notes nor prior preparation. These talks would eventually constitute the important middle section of the book Poustinia.

The second aspect of the poustinia evolution took form during a visitation to Stella Maris, our Madonna House in Portland, Oregon in March 1968.

Catherine wrote, “Quite unexpectedly and almost without knowing that I was saying, yet realizing that I was saying it, I put the following question to everyone — what if the Lord means this house to be a poustinia in the marketplace?!

“…Nothing would change … But everything would be changed in depth. Living in the poustinia of their house would mean three people standing still before God in order to walk with men. The door of their hearts, as the door of their home, must henceforth never be closed” (Poustinia, pp.57, 58).

This was the beginning of what came to be called “poustinia houses” — Madonna House foundations, staffed by two or three people, with a mandate to pray and fast in the poustinia for the diocese in which they lived, for the Church and for the world, and to welcome others who wished to spend twenty-four hours in this way.

Between 1973 and 1985, 15 poustinia houses were opened in Canada, the US, Barbados, and France.

While trying to communicate the essence of the Russian tradition, Catherine did not attempt to simply replicate its form. Each poustinia house would develop its own character, she explained, its own “face.” She reminded them, however, “There is only one reason for going to the poustinia and that is to meet God in great silence.”

In July 1973, Catherine wrote, “You might have heard that Fr. Bob Wild is correlating and editing my book on poustinia. The first part is ready and we are reading it at noon.” The manuscript was bought by Ave Maria Press and in early January 1975, Poustinia: Eastern Christian Spirituality for Western Man was published as a Book-of-the-Month selection.

The response was immediate. Only two years after its publication, Poustinia was already in its sixth printing and had sold 67,000 copies. The British edition had sold an additional 20,000 copies. The French translation by the Dominican priest Fr. Jean Prignaud was awarded a prize by the Académie Française for the best book translated from a foreign language.

The book was eventually translated into sixteen languages. It went through four editions and 28 printings, becoming a spiritual classic. In 1996 Madonna House Publications acquired the copyright, and with the 3rd edition in 2000, the subtitle was changed to Encountering God in Silence, Solitude, and Prayer. Over and over again, we heard people attest to its influence in their lives.

In 1980, the Spanish translation of Poustinia was sent to all the bishops of Latin America. Among the acknowledgements was one from an Argentinian bishop who wrote, “I hope to be able to read the book but I don’t know when. Why? Because immediately it was grabbed by other people who are passing it from one to the other!”

A bishop in Bolivia told Catherine, “We are… faced with Marxist materialism and I hope to learn in your book how to live the faith in the midst of the vicissitudes of this world that hates the Lord.”

In France, Poustinia found an immediate response, resonating in people’s hearts as if it provided a balance to the intellectualism of French culture and leading to the opening of a poustinia house in Paris in 1985. It is striking that Madonna House in France was always known primarily as la Communauté de Poustinia.

The last chapter of the book speaks of the poustinia of the heart, a state of interiorization where one no longer needs the physical poustinia because he or she carries within them the presence of the Lord and goes forth as a pilgrim, a strannik, to bring that presence to their brothers and sisters all over the world. The result is sobornost, union. This is the goal of the poustinia.

Since Catherine’s death in 1985, the word “poustinia” has become part of the Catholic spiritual vocabulary. An Internet search reveals countless prayer houses that offer desert days or more specifically “a poustinia experience.” At the Madonna House centre in Combermere, Ontario, there are something like twenty poustinias available to members as well as guests.

The poustinia spirituality described in the central section of the book has become integrated into the spiritual life of Madonna House members, part of the journey to the heart of Christ.

It is in Nazareth, the locus of everyday life, that kenosis takes place, as well as atonement. Not only is prayer a form of service but it is the essential condition of service. “To become a prayer,” a phrase dear to Catherine, is in some ways analogous to the poustinia of the heart.

“The essence of the poustinia is that it is a place within oneself, a result of baptism, where each of us contemplates the Trinity. Within my heart, within me, I am or should be constantly in the presence of God. … Thus, everything that I have said about the physical poustinia, about trying to adapt it to the West, can be said about every Christian everywhere.

“The poustinia is this inner solitude, this inner immersion in the silence of God. It is through this inner, total identification with humanity and with Christ that every Christianshould be living in a state of contemplation. This is the poustinia within oneself” (Poustinia, pp.184, 185).

* From Journey Inward, by Catherine de Hueck Doherty, Alba House, New York 1984, out of print.

Excerpts from Poustinia are from the fourth edition, 2021, available from Madonna House Publications.