It’s a story many people struggle with and shy away from

– the command from God to Abraham to offer his son, his beloved, as a human sacrifice. The Second Sunday of Lent (February 25) brings us, along with the traditional Gospel of the Transfiguration (Mark 9), the account of Abraham and Isaac from Genesis 22: Abraham’s seemingly unconditional and immediate obedience; and then the last minute staying of his hand and provision of another offering, the ram. It was all just a test of Abraham’s faith.

For obvious reasons, this appalls us. What God commands a parent to kill their own child? What parent kills their own child at God’s behest? What kind of test is this? I sincerely doubt that this story has ever been an easy, comfortable read for Jews or Christians of any era, but to our modern ears it just sounds horrific.

To compound that basic level of shock and outrage, it is worth noting that God has made it painstakingly clear to Abraham that Isaac is the son who will establish a people that will endure to the ages of ages.

Abraham already had his son Ishmael, but God has revealed that only Isaac will be the founder of the chosen people of God, the people who will inherit the land. And now Isaac is to be killed. What is going on here?

Of course, we can say clearly that the all-powerful, all-knowing God knows well (and in fact has infinite power to ensure it) that Abraham’s hand will be stayed, that nothing will happen to Isaac, that all will end well in this episode.

Scripture scholars tell us that child sacrifice was a common feature of the religious rites of the neighboring tribes, and that, in fact, an original meaning and purpose of this story was to clarify that this was in no way or form to be the religious practice of the God of Abraham and Isaac.

Well… that’s nice, I guess. But they hardly remove the sense of horror any reasonable, thoughtful person will feel, reading this account. We still have this strange image of a father tying his son to an altar and raising a knife to take his life. We still have to grapple with a God who engineered such a scene. What is going on here?

I won’t attempt in this article to provide some glib, smooth exegesis of this text that will make everything just fine and dandy and not a problem for us.

Besides being far beyond my capacities as a writer, it also would miss the whole point of this story and what it is supposed to mean for us, what light it can shed into our lives and choices and in our following of this same God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob… and Jesus.

It is worth pondering what the Abraham story would look like if we didn’t have Genesis 22 as part of it. It would run more or less like this: God appears to man, promises to make him father of a great nation, and gives him land. Man follows God to that land, has a son, and becomes father of a great nation, and his descendants inherit the land. The end.

It’s a nice story, but a bit boring, don’t you think? “Chaldean man makes good.” Hurray for Abraham, but this is not exactly a story that resonates unto the ages. It is this episode with Isaac on Mount Moriah that makes it the story not only of Abraham but of us all.

The sacrifice of Isaac transposes the entire story of Abraham to the level of mystery, mysticism, and deep, dark faith. God promises; God acts. God is doing something in the world, in all of our lives, but he does it in a way that confounds, baffles, and mystifies us. And that often causes us tremendous distress.

God is acting, God is faithful, God is good… but so often the ways of God are not only mysterious to us but are very painful. Sacrifices are asked. Losses are endured. It doesn’t make sense. It doesn’t seem right. Is God good? Where is his goodness? Is he a loving Father, and are we really his beloved sons and daughters?

These are all real questions that almost everyone has to wrestle with at some point in their lives. In the life of the world, it is no different and even more acute. To put it simply, if rather painfully, God may not desire child sacrifice, but there are so very many dead children, nonetheless. Who with a heart does not have their heart broken in that?

For us who believe in a monotheistic system – namely that there is one God and one alone, and that he is sovereign — everything that happens falls under the permissive will of God. He is Lord.

All the outrages, all the atrocities, all the wars and crimes and violence, and all the personal tragedies – sudden deaths, illness, infirmity – all of it is allowed by God, even, in a sense, “willed” by him in his divine permission which is absolute.

If we don’t believe that, we no longer believe in the God of Abraham and Jesus. But believing it means grappling with the constant mystifying, bewildering, confounding, and quite often very painful working out of God’s plan for humanity and for you and for me individually.

Abraham, standing at the very head of all the monotheistic believers to come, is called to confront this most directly and painfully in the Isaac episode on the mount.

No, it doesn’t make sense, and it’s not really OK, and any attempt to explain Genesis 22 in a way that makes it make sense, and “all be OK,” truly distorts what the Lord is telling us here. It obscures the question of why this story is in our Bibles and why we need to not shy away from it entirely.

Abraham is called to make an act of utter trust and faith in the God who, despite all seeming appearances, not only loves him but loves Isaac as much as he does. Isaac is not only Abraham’s beloved son but God’s beloved son, too. And so, we are all called to make that deep act of faith in the face of our own calamitous losses, personal tragedies, and world events of horror and death.

At the heart of this mystery is the Beloved Son of God, who was not spared, and who is, in fact, the “ram” God provided as the sacrificial offering for all humanity.

We cannot come to grips with the paradox of a loving and good God working out his designs in a world full of evil and darkness without embracing that paradox of all paradoxes – the death of God in Jesus Christ – as the definitive moment of light, love, and life, conquering darkness, hate, and death.

It doesn’t make sense, not in the way we want it to, and our minds will never be satisfied with any kind of explanation we can come up with. But our hearts can come to rest before the crucifix, the tabernacle, the altar, the Lord.

In this Lenten time, and in all the trouble of our world at this time, let us rest there and find the faith and hope we need to journey in love to the Promised Land, the Kingdom of heaven. There (and only there) all shall be made well for us and for the world.

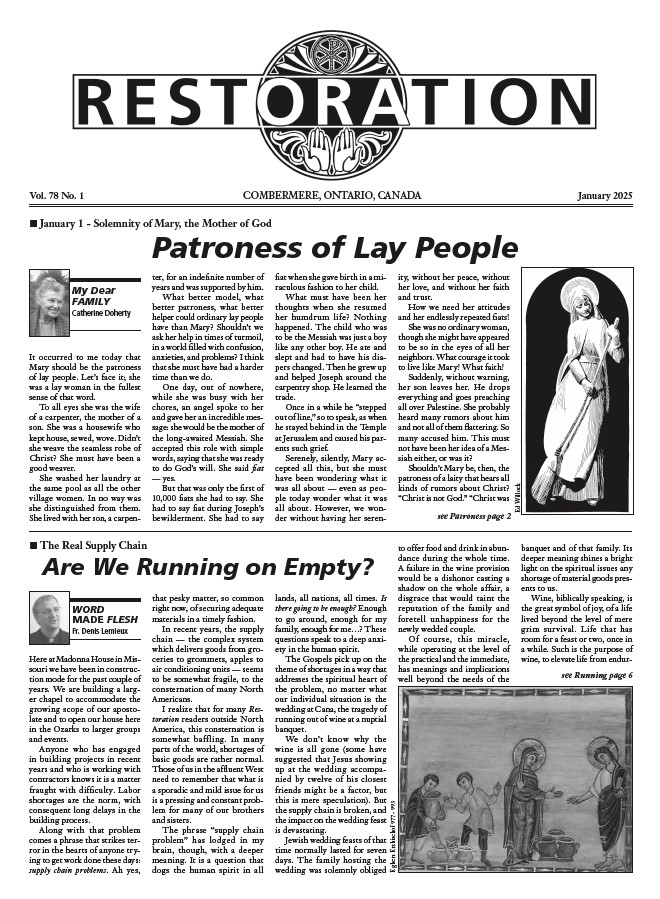

image: Sacrifice of Isaac by Caravaggio